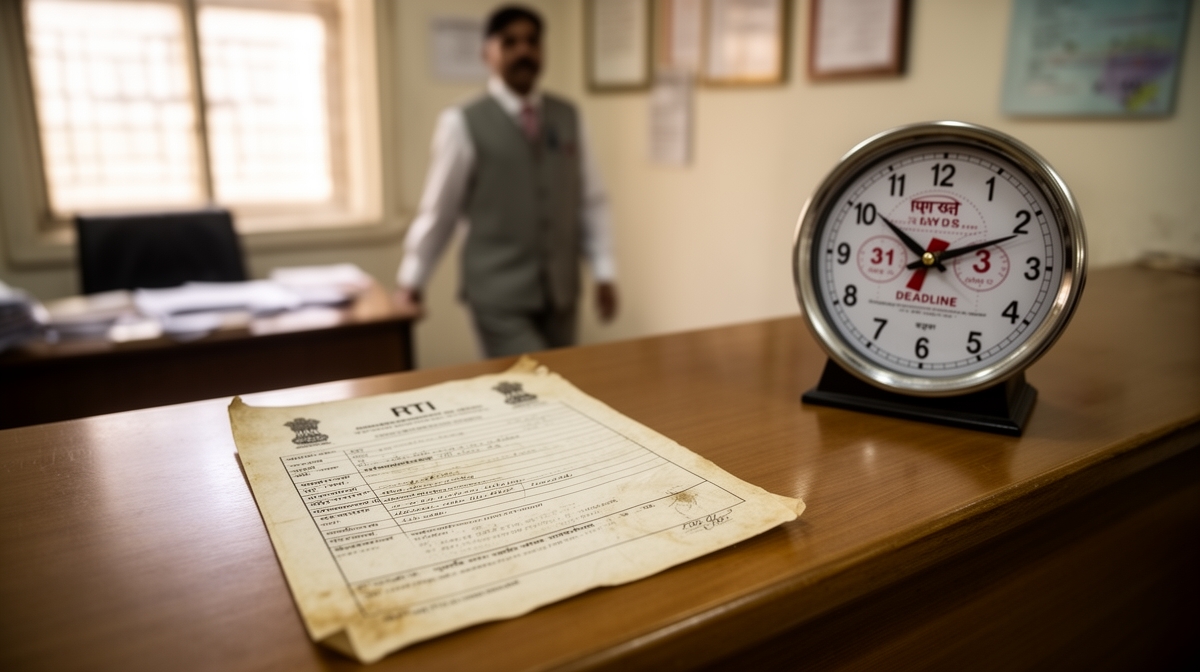

The Central Information Commission has directed a public authority to facilitate physical inspection of records when an applicant disputes the completeness of information provided under the RTI Act. The Commission emphasized that mere provision of documents does not discharge the obligation of transparency if the applicant reasonably challenges the adequacy of the response.

The Verdict

The Appellant won. The Central Information Commission held that when an applicant contests the completeness and veracity of information provided under the RTI Act, the public authority must facilitate physical inspection of relevant records. The Commission directed the CPIO to provide a list of files, arrange them for inspection, and allow the Appellant or his representative to examine originals within two weeks, with certified copies available on payment of prescribed fees. This ensures compliance with the principle of maximum disclosure under the RTI Act.

Background & Facts

Mohan Lal Purohit, a retired Senior Section Engineer re-engaged by the North Western Railway, filed an RTI application on 1 February 2024 seeking four categories of information related to his remuneration and the Railway Board’s policies. He sought photocopies of departmental notings on his representations, comments on a similar case from Western Railway, notings on a Ministry of Finance memorandum, and the specific Railway Board rule justifying the exclusion of frozen dearness allowance (DA) from his re-engagement pay.

The CPIO responded on 9 May 2024, referencing existing circulars and stating that no further documents existed. The First Appellate Authority upheld this response on 21 May 2024, adding that some documents fell outside the jurisdiction of the North Western Railway. The Appellant, dissatisfied, filed a second appeal with the Central Information Commission on the same day.

During the hearing, the Appellant challenged the credibility of the information provided, alleging that key documents were withheld. He argued that the CPIO’s reliance on external circulars without producing internal notings or decision-making records was inadequate. The Respondent maintained that all relevant documents had been furnished and that the Appellant’s concerns were essentially grievances about pay, not genuine RTI requests.

The Commission noted that while the Respondent had provided copies of policy documents, there was no evidence that internal departmental records - such as noting sheets, comments by Personnel Officers, or file trails - had been made available for inspection. Crucially, the Appellant had not been given an opportunity to verify the completeness of the records.

The Legal Issue

Does the mere provision of copies of policy circulars satisfy the obligation under the RTI Act when an applicant disputes the completeness of the information and alleges suppression of internal departmental records? Is physical inspection of original files mandatory when the adequacy of the response is contested?

Arguments Presented

For the Petitioner

The Appellant contended that the CPIO’s response was incomplete and evasive. He argued that Section 6(1) of the RTI Act imposes a duty to provide information in the form requested, and that merely citing external circulars without producing internal notings, file trails, or decision-making records violates the spirit of transparency. He relied on Section 4(1)(b) of the RTI Act, which mandates proactive disclosure of decision-making processes, and cited the Supreme Court’s judgment in CIC v. State of Bihar (2019), which held that the right to information includes the right to inspect records to verify authenticity. He further argued that the CPIO’s failure to produce internal notings on his representations suggested concealment.

For the Respondent

The Respondent submitted that all relevant documents held by the public authority had been provided. It argued that the referenced documents from Western Railway and the Ministry of Finance were not its records under Section 2(f) of the RTI Act, and therefore could not be disclosed. It further contended that the policy on re-engagement was governed solely by RBE No. 150/2017 and the Ministry’s OM dated 23.04.2020, both of which had been shared. The Respondent maintained that the Appellant’s request was essentially a grievance about pay revision, not a legitimate RTI query, and that no additional records existed beyond those already furnished.

The Court's Analysis

The Commission rejected the Respondent’s argument that the Appellant’s request was merely a grievance disguised as an RTI application. It held that the nature of the request - seeking specific documents and notings - falls squarely within the scope of Section 6 of the RTI Act, regardless of the Appellant’s underlying motive. The Commission emphasized that the Act’s primary objective is transparency and accountability, and that the burden lies on the public authority to prove that no further records exist.

"The mere provision of policy documents does not discharge the obligation under the RTI Act when the applicant challenges the completeness of the response. The right to information includes the right to inspect original records to verify their authenticity and completeness."

The Commission distinguished between the provision of copies and the obligation to facilitate inspection. It noted that while copies of external circulars were provided, the Appellant specifically sought notings and comments made by the Personnel Branch and Office Superintendent on his representations - internal records that are presumptively held by the public authority. The Respondent failed to demonstrate that such records did not exist.

The Commission further held that Section 8 and Section 10 of the RTI Act permit withholding only specific categories of information, such as third-party data or exempted records. The absence of such claims in the Respondent’s reply indicated that no valid exemption applied. Therefore, the only way to resolve the dispute was to allow inspection.

The Commission also noted the procedural lapse: the Respondent had not served a copy of the second appeal, but since the matter was heard on merits and the Respondent participated, the defect was waived.

What This Means For Similar Cases

This decision establishes a clear precedent: when an RTI applicant challenges the adequacy of the information provided - particularly by alleging suppression of internal notings, file trails, or decision-making records - the public authority must facilitate physical inspection of relevant files. Mere provision of copies of policy documents is insufficient if the applicant questions whether all internal records have been disclosed.

Practitioners should now treat such challenges as triggering an obligation to offer inspection, not just re-send documents. Public authorities must maintain organized records with file numbers, subject headings, and page counts to enable prompt compliance. Failure to do so may result in adverse orders under Section 19(8)(b) of the RTI Act.

This ruling also reinforces that the motive behind an RTI request is irrelevant. Even if the applicant seeks information to support a grievance or litigation, the authority must respond to the request on its merits. The burden of proving non-existence of records rests entirely on the public authority.

The directive to provide a list of files before inspection sets a new standard for procedural fairness. It prevents fishing expeditions while ensuring transparency. Practitioners should advise clients to request such lists proactively in future appeals.