The Central Information Commission has delivered a stern reaffirmation of the statutory obligations under the Right to Information Act, 2005, emphasizing that non-response within the prescribed time is not mere procedural lapse but a substantive violation warranting accountability. This judgment clarifies the consequences of institutional inertia and reinforces the primacy of timely disclosure in a democratic governance framework.

Background & Facts

The Dispute

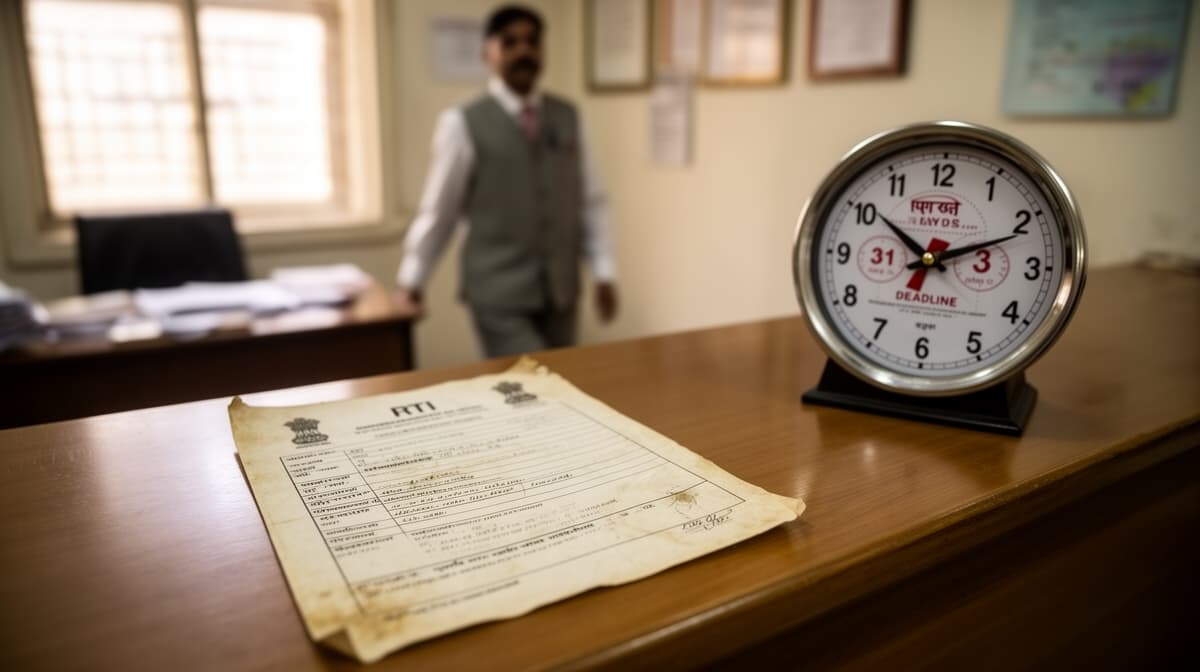

The appellant, an RTI applicant, filed a request on 22 May 2024 seeking information regarding expenditure incurred by the Delhi Government’s Department of Irrigation and Water Resources on flood relief measures in 2023. The request sought details on expenditure, invoices, and related documents across four districts: East, West, North-East, and Central.

Procedural History

- 22 May 2024: RTI application submitted to Delhi Government’s Public Information Officer (PIO).

- No response received within the statutory 30-day period.

- 16 July 2024: First appeal filed before the First Appellate Authority (FAA).

- No order issued by the FAA within any reasonable time.

- 20 September 2024: Second appeal filed before the Central Information Commission (CIC).

Relief Sought

The appellant sought: (1) a direction to the concerned PIOs to provide the requested information; (2) a penalty under Section 20 of the RTI Act against the responsible officials for willful delay and non-compliance; and (3) a directive to ensure systemic compliance with statutory timelines.

The Legal Issue

The central question was whether Section 7(1) of the Right to Information Act, 2005 imposes a mandatory duty on Public Authorities to respond within 30 days, and whether failure to do so - without any valid exemption - constitutes a breach warranting penalty under Section 20, even if information is eventually provided belatedly.

Arguments Presented

For the Appellant

The appellant argued that the absence of any response within 30 days, as mandated by Section 7(1), automatically triggers the right to file an appeal and exposes the Public Authority to penalties under Section 20. He cited State of U.P. v. Raj Kumar and Smt. Sunita Devi v. CIC to establish that delay, regardless of eventual compliance, undermines the spirit of the Act. He emphasized that the belated response received on 5 March 2025 was incomplete and misleading, directing him to inspect documents physically - an impractical condition.

For the Respondent

The Respondent PIOs, represented by officials from East, North-East, and Central Districts, contended that the application was forwarded to the concerned departments under Section 6(3), and that the response issued on 5 March 2025 was sufficient. They argued that the delay was due to administrative backlog and internal miscommunication, not malafide intent. They further claimed that the appellant had been given access to documents during physical inspections, and therefore, no penalty was warranted.

The Court's Analysis

The Commission conducted a rigorous analysis of the statutory framework under the RTI Act, 2005, particularly Sections 6(3), 7(1), and 20(1). It held that Section 7(1) is not directory but mandatory, and the 30-day window is a statutory deadline designed to uphold the right to timely information. The Commission rejected the argument that belated compliance negates liability, stating:

"The Act does not permit Public Authorities to treat statutory timelines as suggestions. Delay, even if followed by eventual disclosure, defeats the very purpose of the RTI Act, which is to ensure transparency and accountability through promptness."

The Commission distinguished between forwarding an application under Section 6(3) and discharging the duty to respond. While forwarding is permissible, the ultimate responsibility for timely response remains with the designated PIO. The Commission noted that the Delhi Government’s officials failed to respond even after the first appeal, indicating systemic negligence.

It further found the appellant’s claim of being misled by the response - directing him to inspect documents at offices that were inaccessible - was substantiated by his repeated visits and lack of access. The Commission held that Section 8(1) exemptions were not invoked, and therefore, no legal ground existed for withholding or delaying information.

The Commission also condemned the non-appearance of key PIOs from West and Central Districts during the hearing, despite being served notice, and the absence of any written submissions from them. This, it held, amounted to contempt of the Commission’s authority.

The Verdict

The appellant succeeded. The Commission held that failure to respond within 30 days under Section 7(1) constitutes a violation warranting penalty under Section 20, regardless of subsequent disclosure. It directed the concerned PIOs to provide complete information within 15 days and imposed a procedural penalty framework on non-compliant officials.

What This Means For Similar Cases

Statutory Timelines Are Non-Negotiable

- Practitioners must now treat any delay beyond 30 days as a prima facie violation under Section 20, irrespective of whether information is later provided.

- Appeals should be framed to explicitly invoke Section 20(1) for penalties when deadlines are missed, even if the information is eventually disclosed.

- The burden shifts to the Public Authority to prove that delay was due to exceptional circumstances, not mere administrative inefficiency.

Accountability Extends to Non-Appearing Officials

- Officials who fail to appear before the CIC despite notice, or submit no written reply, are deemed to have admitted non-compliance.

- The Commission may initiate suo motu proceedings under Section 20(2) for contempt and impose maximum penalties of ₹25,000 per defaulting officer.

- Legal representatives must ensure all concerned PIOs are formally served and their non-appearance is recorded in the appeal.

Physical Inspection Cannot Substitute for Document Provision

- Directing applicants to physically inspect documents without providing certified copies violates Section 7(1) and Section 7(9).

- If documents are exempt under Section 8(1), the Public Authority must explicitly cite the exemption clause and provide reasons.

- Merely offering inspection without facilitating access or providing copies is a procedural fraud and grounds for penalty.