The Andhra Pradesh High Court has reaffirmed a foundational safeguard against arbitrary arrest by directing police to strictly comply with pre-arrest notice procedures under Section 41A of the Code of Criminal Procedure for offences carrying a maximum sentence of five years. This ruling reinforces the constitutional imperative against custodial overreach and provides critical clarity for practitioners handling non-heinous criminal complaints.

Background & Facts

The Dispute

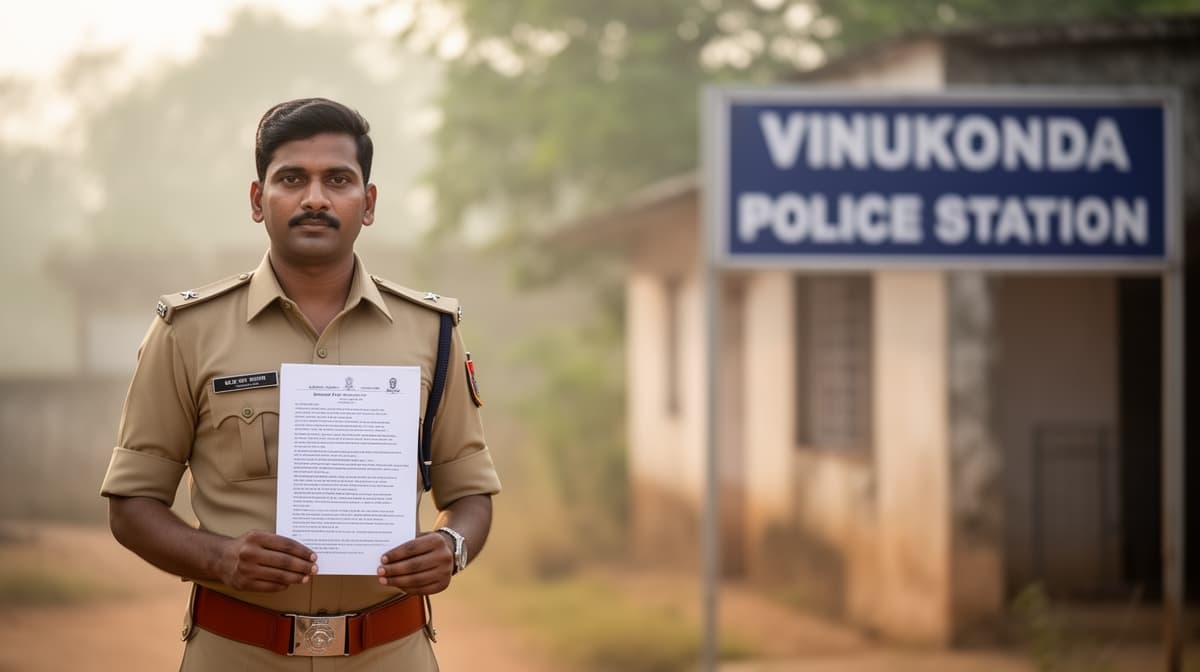

The petitioners, comprising 27 individuals including former elected representatives and local residents, were named as accused in Crime No. 29 of 2026 registered at Vinukonda Police Station. The allegations pertained to offences under Sections 189(2), 126(2), 121(1) read with 190 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, which collectively attract a maximum punishment of five years’ imprisonment. The petitioners sought protection from coercive police action, including arrest, without adherence to statutory pre-arrest procedures.

Procedural History

The petition was filed under Section 528 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, challenging the proposed arrest of the accused without prior compliance with procedural safeguards. No chargesheet had been filed at the time of filing. The petitioners did not seek discharge or quashing of the FIR, but specifically requested that the police be directed to follow the mandatory pre-arrest notice mechanism.

Relief Sought

The petitioners sought a direction to the police to issue a notice under Section 41A of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, before initiating any arrest, and to comply with the procedural safeguards laid down in Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar.

The Legal Issue

The central question was whether police are obligated to follow the pre-arrest notice procedure under Section 41A of the Code of Criminal Procedure when the alleged offence is punishable with imprisonment of less than seven years, even if the offence is non-bailable.

Arguments Presented

For the Petitioner

Learned counsel for the petitioners argued that since the maximum punishment for the alleged offences does not exceed five years, the conditions under Section 41A CrPC are triggered. They relied on the binding precedent in Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar, which mandates that arrest cannot be the default response for offences punishable by less than seven years. Counsel emphasized that the police must first issue a notice requiring the accused to appear, assess compliance, and record reasons if arrest remains necessary.

For the Respondent

The Assistant Public Prosecutor did not dispute the applicability of Arnesh Kumar but contended that the nature of the allegations - pertaining to public order and official misconduct - warranted immediate investigation and potential arrest. However, the State did not oppose the direction to follow Section 41A, leaving the Court to determine the legal obligation.

The Court's Analysis

The Court examined the statutory framework under Section 41A CrPC, which mandates that before arresting a person accused of an offence punishable with imprisonment of up to seven years, the police must issue a notice under Section 41A(1) requiring the accused to appear before the officer. The Court held that the provision is not discretionary but mandatory, and its purpose is to prevent unnecessary custodial detention.

"The mandate under Section 41A CrPC is not a mere formality but a constitutional safeguard against arbitrary arrest, especially where the gravity of the offence does not justify immediate deprivation of liberty."

The Court further referenced Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar, noting that the Supreme Court had unequivocally held that police officers must satisfy the triple test - (i) necessity of arrest, (ii) possibility of the accused fleeing justice, and (iii) likelihood of tampering with evidence - before resorting to arrest. The Court observed that no such reasons were recorded in the present case, and the mere pendency of an FIR does not justify bypassing Section 41A.

The Court also clarified that the transition from CrPC to BNSS does not dilute the protections under Section 41A, as Section 35 of BNSS is the direct counterpart and carries identical intent and scope.

The Verdict

The petitioners succeeded. The Court held that Section 41A CrPC applies mandatorily to offences punishable with imprisonment of up to five years, and directed the police to strictly follow its procedures before any arrest. The petition was disposed of with this direction, and all pending miscellaneous petitions were closed.

What This Means For Similar Cases

Arrest Is Not Automatic for Non-Heinous Offences

- Practitioners must now routinely invoke Section 41A CrPC in all cases where the maximum punishment is seven years or less, regardless of whether the offence is bailable or non-bailable.

- Police failure to issue a Section 41A notice before arrest renders the arrest procedurally invalid and may attract liability under Section 220 CrPC for wrongful confinement.

Documentation of Reasons Is Non-Negotiable

- If arrest is deemed necessary after notice, the police must record specific, case-specific reasons justifying deviation from the notice procedure.

- Courts will not accept generic statements like "risk of tampering" without factual basis; the burden lies squarely on the investigating officer.

BNSS Does Not Override CrPC Safeguards

- Even under the new Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, Section 35 mirrors Section 41A CrPC in substance.

- Lawyers should cite both provisions in petitions to reinforce that statutory protections remain intact post-reform.