The Chhattisgarh High Court has directed authorities to reconsider the reinstatement of a terminated daily-wage watchwoman, emphasizing that denial of opportunity in the face of available posts and funds, while others were accommodated, amounts to arbitrariness and discrimination. The judgment reinforces the principle that administrative decisions affecting livelihood must be guided by fairness, especially when termination occurred due to external financial constraints beyond the employee’s control.

The Verdict

The petitioner won. The Chhattisgarh High Court held that a daily-wage employee terminated during the COVID-19 pandemic due to funding constraints cannot be permanently excluded from reinstatement if similar positions later become available and funds are sanctioned. The Court directed the authorities to reconsider her case afresh within four weeks, ensuring parity with other similarly situated employees who were reinstated.

Background & Facts

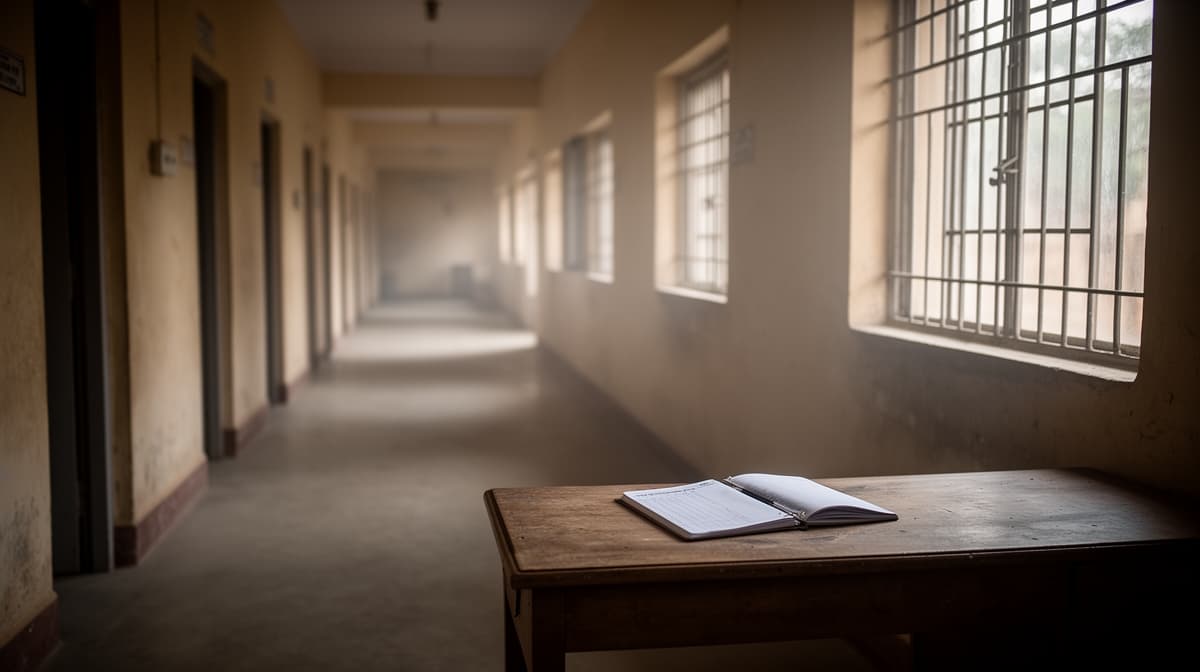

The petitioner, Smt. Dulari Yadav, was appointed as a daily-wage Watchman at the 100-seater Girls Hostel in Bhaiyathan, Surajpur, on 5 September 2019 under a Centrally Sponsored Scheme funded by the Ministry of Education, Government of India. She served diligently for over two years without any adverse remarks. Her services were terminated on 31 August 2021 by the Hostel Superintendent, citing non-availability of funds for honorarium payments. The termination was effected without notice or opportunity of representation.

Subsequently, on 1 September 2021, the State Government issued a circular directing Collectors and District Mission Directors to accommodate discontinued peons, watchmen, and cooks in other hostels where vacancies existed. The petitioner submitted representations seeking accommodation in line with this directive, but her requests were ignored. She approached the Court in W.P.(S) No. 9186/2022, which was disposed of on 3 January 2023 with a direction to the District Collector and District Education Officer to consider her case in accordance with rules and the 1 September 2021 circular.

Despite compliance with the Court’s order, the petitioner’s representation was rejected on 18 April 2023 by the Managing Director, Samagra Shiksha, on the ground that no sanction had been obtained from the Central Government to continue the scheme. Meanwhile, records show that other similarly placed employees had been reinstated in comparable circumstances. The post of Watchman at the Bhaiyathan Hostel remained vacant, and no formal order abolishing the post was produced before the Court.

The Legal Issue

The central question was whether a daily-wage employee, terminated due to temporary funding constraints during the pandemic, can be permanently denied reinstatement when similar posts become available and funds are sanctioned, especially when other similarly situated employees have been accommodated.

Arguments Presented

For the Petitioner

The petitioner’s counsel argued that her termination was not due to misconduct or inefficiency but solely due to financial constraints beyond her control. She had served for over two years with unblemished record. The State’s own circular dated 1 September 2021 mandated accommodation of such employees in other hostels. The Court’s earlier direction on 3 January 2023 was binding and had been implemented for others. Denying her reinstatement while others were reinstated violated the principle of equality under Article 14 and amounted to arbitrariness. The absence of a formal order abolishing the post rendered the denial of opportunity legally unsustainable.

For the Respondent

The State contended that the petitioner’s engagement was under a Centrally Sponsored Scheme, and her services were terminated due to non-availability of funds from the Central Government. No post was currently available for her, and no sanction had been granted by the Government of India to revive the scheme. The rejection of her representation on 18 April 2023 was based on this factual and financial reality. The earlier Court direction was complied with by examining her case, and the decision not to reinstate was based on the absence of sanctioned funds, not discrimination.

The Court's Analysis

The Court acknowledged that the petitioner’s engagement was on a daily-wage basis under a Central Scheme, and her termination was triggered by funding discontinuance during the pandemic. However, the Court emphasized that termination due to external financial constraints does not extinguish the right to be considered for reinstatement if circumstances change. The absence of a formal order abolishing the post was critical - the State could not rely on mere non-availability of funds to permanently bar reinstatement.

"The petitioner’s services were terminated under exceptional circumstances beyond her control, and her right to be considered for reinstatement, if funds and posts are available, cannot be ignored."

The Court noted that other employees in identical circumstances had been reinstated, establishing a clear pattern of administrative practice. Denying the petitioner the same opportunity without objective justification violated the doctrine of equality and non-arbitrariness under Article 14. The Court rejected the State’s argument that compliance with the earlier order was complete merely by reviewing the representation. True compliance required a meaningful reconsideration in light of changed circumstances.

The Court further observed that the pandemic period warranted a compassionate administrative approach. The fact that the post remained vacant and no formal abolition order existed meant the possibility of reinstatement was not foreclosed. The authorities were therefore directed to reassess her case with a reasoned order, ensuring parity with others.

What This Means For Similar Cases

This judgment establishes a significant precedent for daily-wage and contract workers terminated during the pandemic due to funding constraints. Practitioners representing such employees can now invoke this ruling to demand reconsideration of reinstatement when posts become available and funds are sanctioned, even if the original engagement was under a Central Scheme. The judgment clarifies that administrative inaction or passive non-availability of funds does not equate to permanent abolition of a post.

The principle of parity is now firmly entrenched: if similarly situated employees are reinstated, denial to one without objective, documented justification will be struck down as arbitrary. This applies not only to educational hostels but to any government-funded scheme where daily-wage workers were let go due to temporary financial disruptions. Practitioners should now routinely request copies of post-abolition orders and track fund sanctions to build strong cases for reinstatement. The four-week timeline for a speaking order sets a clear benchmark for administrative accountability.