The Bombay High Court has affirmed that prolonged, unexplained absence - supported by official documentation and public notice - suffices to invoke the legal presumption of death under Section 108 of the Indian Evidence Act. This ruling clarifies that no medical or testimonial proof of mental incapacity is required, reinforcing the statutory framework for declaring a person dead in civil proceedings.

Background & Facts

The Dispute

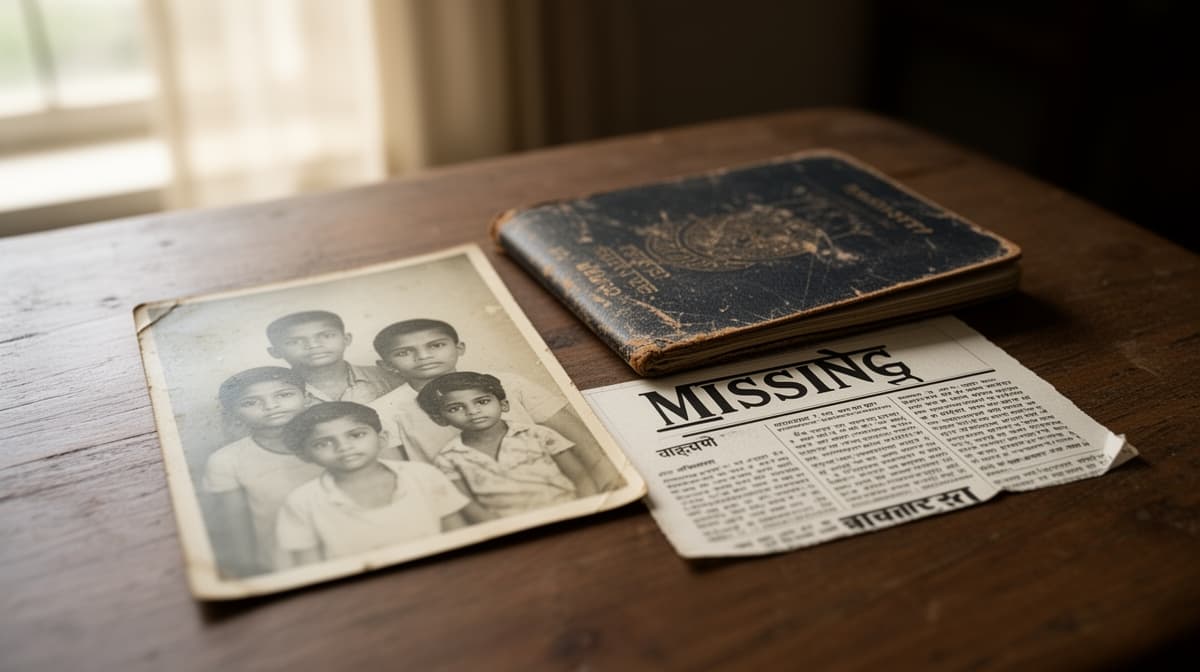

The appellant, Vishwesh Dogra Suvarna, sought a judicial declaration that his father, Mr. Dogra Venkappa Survarna, was legally dead after being missing since 8 April 2003. The father vanished during a medical check-up in Mumbai and was never seen again. The appellant filed a civil suit seeking a declaration of death to facilitate inheritance, property transactions, and closure of legal affairs.

Procedural History

- April 2003: Mr. Dogra Survarna went missing; police complaint filed

- November 2011: Police issued a certificate confirming the person remained untraceable after eight years

- 2015: Trial Court dismissed the suit, citing lack of medical evidence of memory loss and absence of proof regarding other legal heirs

- 2016: First Appeal filed before the Bombay High Court

Relief Sought

The appellant sought a declaration under Section 108 of the Indian Evidence Act that his father was presumed dead as of 8 April 2010 - seven years after his disappearance.

The Legal Issue

The central question was whether the presumption of death under Section 108 of the Indian Evidence Act can be invoked solely on the basis of seven years of unexplained absence, supported by police certification and public notice, even in the absence of medical evidence or proof of no other heirs.

Arguments Presented

For the Appellant

The appellant’s counsel relied on Section 108 of the Indian Evidence Act, which permits a presumption of death if a person has not been heard of for seven years by those naturally expected to hear from him. They submitted that the police certificate, newspaper advertisements in Marathi and Kannada, and official documents (passport, ration card, birth certificate) issued by state and central authorities collectively constituted credible circumstantial evidence. They argued that the burden shifted to the State to disprove the presumption, which it failed to do.

For the Respondent

The State contended that the appellant had not established the absence of other legal heirs and had not produced medical records to show the father’s mental deterioration. It argued that the presumption under Section 108 required more than mere non-appearance and that the Trial Court was correct in demanding corroborative evidence of incapacity.

The Court's Analysis

The Court examined the nature of the presumption under Section 108 of the Indian Evidence Act, noting that it is a rebuttable presumption of fact, not a conclusive one. The Court emphasized that the provision does not require proof of mental condition, illness, or absence of other heirs. The statutory language focuses exclusively on the duration of absence and the likelihood of communication.

"If a person is not heard of by those who would naturally have heard of him if he had been alive, for seven years, it is presumed that he is dead."

The Court held that the police certificate, issued by a state officer under official duty, was a reliable document under Section 35 of the Indian Evidence Act. The newspaper advertisements, published in regional languages across two states, demonstrated active efforts to locate the missing person. The official documents - passport (Union of India), ration card (State), and birth certificate (Karnataka) - were uncontested and corroborated identity and familial relationship.

The Trial Court’s insistence on medical evidence of memory loss was legally misplaced. The Court observed that Section 108 applies to any unexplained absence, whether due to accident, voluntary disappearance, or death. The absence of evidence from the State to rebut the presumption was fatal to its case.

The Verdict

The appellant won. The Bombay High Court held that Section 108 of the Indian Evidence Act was fully satisfied by seven years of unexplained absence, supported by official police certification and public notice. The suit was allowed, and a declaration was granted that Mr. Dogra Venkappa Survarna was presumed dead as of 8 April 2010.

What This Means For Similar Cases

Presumption of Death Requires No Medical Proof

- Practitioners need not produce medical records, psychiatric evaluations, or evidence of dementia to invoke Section 108

- The focus is strictly on duration of absence and likelihood of communication

- Any credible evidence of prolonged non-appearance suffices

Official Documents Carry Weight

- Police certificates, ration cards, passports, and birth certificates issued by state or central authorities are admissible and presumptively reliable

- These documents can establish identity and absence without additional testimony

- Opposing parties must actively rebut such documents, not merely demand more evidence

Public Notice Is a Valid Circumstantial Indicator

- Newspaper advertisements in regional languages, especially when repeated, demonstrate due diligence

- Courts will view such efforts as evidence of genuine attempts to locate the missing person

- Failure to publish may weaken a claim; publication strengthens the presumption