The Jharkhand High Court has affirmed that digital land records must be a true and accurate reflection of official documentation, not an independent or superior source of title. In a decisive writ petition, the Court ordered immediate correction of erroneous online entries and mandated issuance of Khatiyan and rent receipts to a long-standing tenant, reinforcing the primacy of substantive land records over digital interfaces.

Background & Facts

The Dispute

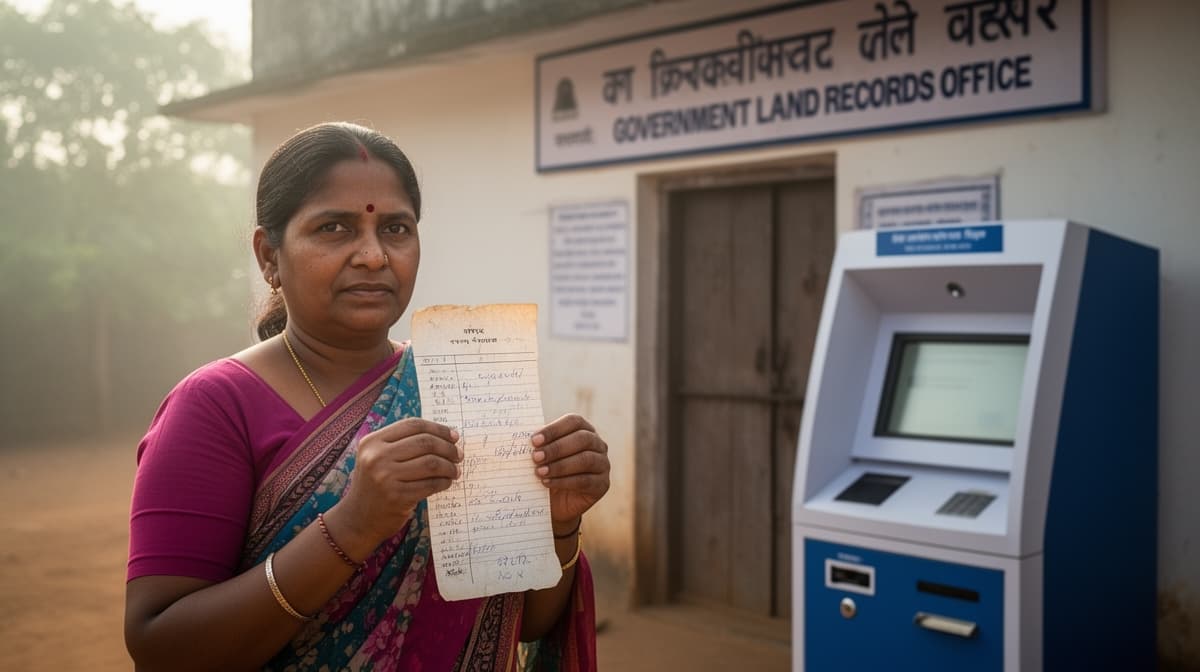

The petitioner, Tita Kumari @ Laxmi Shaw, has been in continuous possession and payment of rent for a plot of land measuring 33 decimal in Mouza Barmasiya, Circle Baghmara, District Dhanbad, since at least 1970. Rent receipts were issued to her until 2012, after which they were withheld on the ground that the land had not been entered into the state’s online land record system. The petitioner has no dispute over her tenancy rights or payment history; the issue is purely administrative failure to update digital records.

Procedural History

- The petitioner submitted multiple representations to the Circle Officer, Land Reforms Department, and Settlement Officer between 2018 and 2025 seeking correction of the online record.

- All representations remained unaddressed or were dismissed without substantive review.

- No formal order was passed denying her claim; instead, officials cited non-existence of online entry as a reason to withhold rent receipts and deny recognition of her rights.

- Faced with persistent denial of basic administrative services, the petitioner filed a writ petition under Article 226 of the Constitution.

Relief Sought

The petitioner sought: (1) a writ of mandamus directing respondents to make accurate online entry of her land; (2) issuance of continuous Khatiyan (Adhikar Abhilekh); (3) issuance of rent receipts; and (4) directions to cease harassment and procedural evasion.

The Legal Issue

The central question was whether the absence of an online entry in the state’s digital land record system can legally justify denial of established tenancy rights, rent receipts, and official recognition, when the petitioner’s possession and payment history are undisputed and documented in physical records.

Arguments Presented

For the Petitioner

The petitioner’s counsel argued that online records are merely a digitized interface, not a source of title or tenancy rights. Reliance was placed on State of Bihar v. Lalit Kumar and Union of India v. Rameshwar Prasad, which held that digital records must reflect substantive legal documents, not override them. The petitioner had produced rent receipts, revenue records, and possession evidence dating back over five decades. The failure to digitize was a systemic administrative lapse, not a legal bar to her rights.

For the Respondent

The State and BCCL contended that the online Khatiyan is the authoritative record under the Jharkhand Land Records Modernization Project. They argued that without digital entry, no rent receipt could be issued, and no official recognition could be granted. They claimed the petitioner had not submitted the requisite application in the prescribed format, though no such requirement was cited in any statute or rule.

The Court's Analysis

The Court rejected the State’s contention that digital records are primary or self-sufficient. It emphasized that the purpose of digitization is to enhance transparency and accessibility, not to create new legal thresholds for established rights. The Court observed:

"The online portal is a tool for public service, not a gatekeeper of rights. To deny a tenant her rent receipt and Khatiyan because of a bureaucratic failure to digitize, when her possession and payment are beyond dispute, is to elevate procedure over justice."

The Court noted that the petitioner’s rights were recognized in physical revenue records, and the State had no statutory authority to condition recognition on digital entry. It further held that persistent non-action on repeated representations amounted to administrative arbitrariness, violating Article 14 of the Constitution. The Court also rejected the notion that the petitioner bore any burden to initiate digitization; the duty lay squarely with the State.

The Verdict

The petitioner succeeded. The Court held that online land records must accurately reflect official documentation, and directed the State to make immediate entry of the land in the digital system, issue the continuous Khatiyan, and provide rent receipts within six weeks. Failure to comply would attract a litigation cost of Rs.10,000 to be recovered from responsible officials.

What This Means For Similar Cases

Digital Records Are Not Primary Evidence

- Practitioners must argue that digital land records are secondary to physical revenue records under the Jharkhand Land Revenue Code and the Indian Evidence Act.

- Any denial of rights based solely on non-availability online is legally unsustainable if substantive proof exists.

State Has Duty to Digitize, Not Citizen to Compensate for Failure

- The burden of updating digital records lies with the State, not the landholder.

- Petitioners in similar cases may now seek mandamus not just for correction, but for systemic compliance under Article 21 (right to access public services).

Litigation Costs as Deterrent for Administrative Lethargy

- The Court’s imposition of a Rs.10,000 penalty on the Deputy Commissioner sets a precedent for holding officials personally accountable for non-compliance.

- Practitioners should now routinely pray for litigation costs in writ petitions involving persistent administrative inaction.