The Bombay High Court has reaffirmed that writ jurisdiction under Article 226 cannot be invoked to re-examine factual disputes arising from land consolidation schemes implemented over five decades ago. This judgment underscores the limits of constitutional remedies when substantive rights have been extinguished and third-party interests established.

Background & Facts

The Dispute

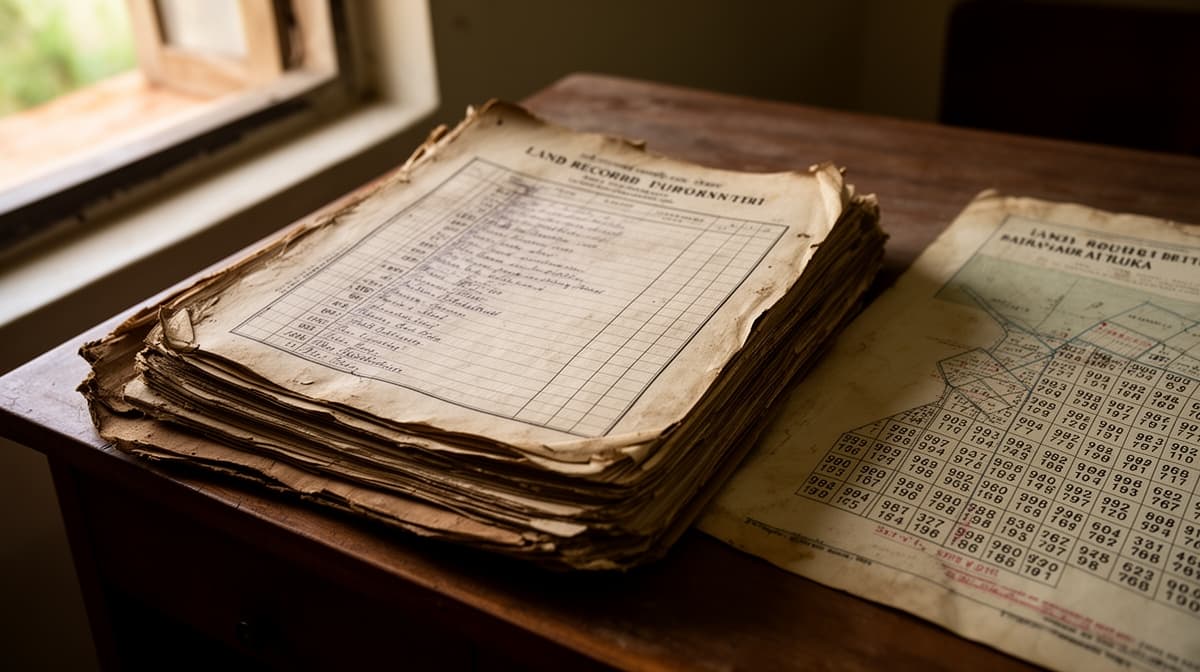

The petitioners, successors to landowners in Nashik, sought to challenge the 1969 Consolidation Scheme under the Maharashtra Prevention of Fragmentation and Consolidation of Holdings Act, 1947. They claimed that a clerical error in the renumbering of Survey No. 38/4A as Gat No. 180 and Survey No. 38/4B as Gat No. 181 deprived them of rightful land area. The challenge was filed in 2022 - 54 years after the scheme was certified and implemented.

Procedural History

- 1969: Consolidation Scheme was formally implemented and certified by the State.

- 2022: Petitioners filed Consolidation Application No. 1774/2022 seeking correction of alleged clerical error.

- 10 October 2024: Deputy Director Land Records (DDLR) dismissed the application, citing laches, finality of the scheme, and creation of third-party rights.

- 2025: Petitioners filed Writ Petition No. 6941 of 2025 before the Bombay High Court seeking to set aside the DDLR’s order.

Relief Sought

The petitioners sought quashing of the DDLR’s order and a direction to rectify the survey numbers to reflect their alleged rightful holdings.

The Legal Issue

The central question was whether a writ petition under Article 226 can be entertained to challenge a land consolidation scheme finalized 54 years prior, where factual disputes regarding entitlement have been settled by statutory process and third-party rights have since accrued.

Arguments Presented

For the Petitioner

The petitioners contended that the error in renumbering was a clerical mistake unknown to them until recently. They relied on the principle of natural justice and argued that the DDLR should have entertained their application despite delay, as the error affected their substantive property rights. They cited State of Maharashtra v. Rameshwar to argue that statutory authorities must correct manifest errors even after long periods.

For the Respondent

The respondents argued that the Consolidation Scheme was a final statutory process under the Maharashtra Act, with a 30-day window for correction explicitly provided. The delay of 54 years amounted to laches and acquiescence. They emphasized that subsequent registered transactions by parties and third parties had created vested rights, which cannot be disturbed in writ proceedings. They relied on K. S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India to affirm that constitutional remedies cannot be misused to circumvent civil remedies.

The Court's Analysis

The Court examined the nature of consolidation schemes under the Maharashtra Act and the statutory framework governing them. It noted that consolidation is not merely administrative but a comprehensive legal process that extinguishes prior rights and substitutes them with new entitlements. The Act provides a clear, time-bound mechanism for correction of errors - 30 days from certification. The petitioners did not avail this remedy.

"The Consolidation Scheme, once certified, operates as a final determination of rights, and any challenge must be raised within the statutory window. Delay of over five decades cannot be condoned, especially when third-party rights have been created on the basis of the certified scheme."

The Court held that writ jurisdiction is not a substitute for civil litigation. Disputed questions of fact - such as whether the petitioners were entitled to more land under their predecessor’s title - require evidence, witness testimony, and detailed adjudication, which are beyond the scope of writ proceedings. The Court further observed that the DDLR’s finding that third-party rights had been created through registered documents was prima facie valid and could not be overturned summarily.

The Verdict

The petitioners lost. The Bombay High Court upheld the DDLR’s dismissal, holding that writ jurisdiction cannot be invoked to re-litigate factual disputes over land entitlements after 54 years, especially when statutory remedies were available and third-party rights have since accrued. The petitioners were directed to pursue their claims in a civil court.

What This Means For Similar Cases

Writ Jurisdiction Is Not a Civil Court Substitute

- Practitioners must not file writ petitions to resolve title disputes or factual claims over land, even if delay is claimed to be innocent.

- Courts will dismiss such petitions summarily if the core issue requires evidence, cross-examination, or adjudication of competing claims.

- The remedy lies in a regular civil suit under Section 9 of the CPC, not under Article 226.

Statutory Finality Trumps Alleged Clerical Errors

- Consolidation schemes under the Maharashtra Act attain finality after the statutory 30-day window.

- Any challenge after this period, particularly after decades, will be barred by laches and the doctrine of acquiescence.

- Courts will prioritize stability of land records and protection of third-party interests over belated claims of error.

Delay in Filing Defeats Remedy

- A delay of 54 years is not merely procedural - it is substantive. Courts will not entertain claims that have lain dormant for generations.

- Petitioners must demonstrate not just ignorance but also due diligence in discovering the error, which was absent here.

- This precedent reinforces that delay defeats remedy in land law, especially where public records and third-party transactions are involved.