The Bombay High Court has denied anticipatory bail to a Village Revenue Officer (Talathi) accused of orchestrating a Rs.25 crore fraud in the disbursement of natural calamity compensation. The Court held that the gravity of the offence, involving systematic forgery of revenue records, fabrication of beneficiary lists, and misuse of official access to government systems, necessitates custodial interrogation to trace the money trail and identify co-conspirators. The applicant’s claim of cooperation and partial recovery was rejected as insufficient to outweigh the scale of the alleged conspiracy and the risk of evidence tampering.

The Verdict

The applicant, a government servant accused of misappropriating over Rs.20 lakh in natural calamity compensation through forged documents and fake beneficiaries, was denied anticipatory bail. The Bombay High Court held that economic offences involving large-scale diversion of public funds, systemic forgery of 7/12 extracts, and manipulation of government databases constitute a class apart requiring stringent bail scrutiny. Custodial interrogation was deemed necessary to trace the money trail, identify co-accused, and recover remaining fraudulent disbursements. The application was rejected.

Background & Facts

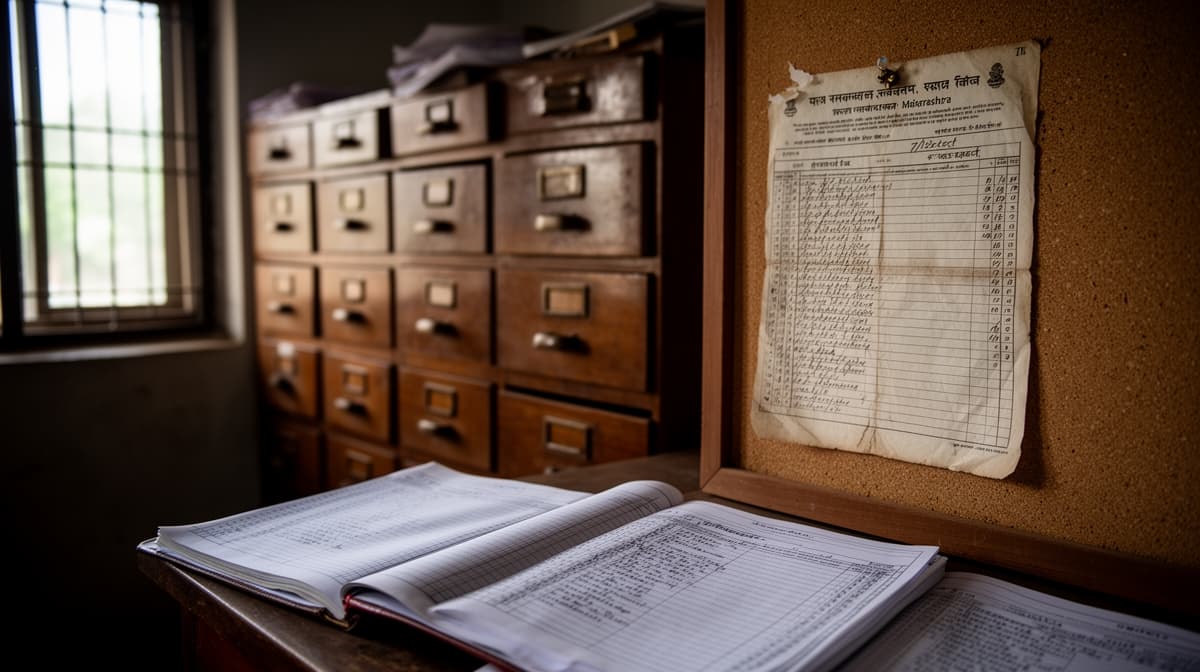

The dispute arises from Crime No.453/2025 registered at Ambad Police Station, Jalna, concerning a widespread fraud in the disbursement of natural calamity compensation to farmers between 2022 and 2024. The State Government had allocated funds to assist farmers affected by floods, drought, and unseasonal rains. However, multiple complaints revealed that Village Revenue Officers (Talathis), Gram Sevaks, and Agricultural Assistants in Ambad and Ghansavangi Talukas had colluded to fabricate beneficiary lists.

The fraud involved forging 7/12 extracts to inflate land holdings, creating fictitious farmer identities, using Aadhaar numbers of non-eligible persons - including laborers and unemployed individuals - lured with small payments, and uploading duplicate or non-resident beneficiaries. The Collector of Jalna constituted a Three-Member Committee in January 2025 to investigate. The Committee’s report identified Rs.24.91 crore in fraudulent disbursements across 28 accused persons.

The applicant, a Talathi posted in Malyachiwadi, was named as a key participant. The Committee alleged she prepared and submitted beneficiary lists containing ineligible persons, including her own relatives and her landlord. She was accused of using her Aadhaar number to claim Rs.48,700 under a fictitious name (Mangal Dhaka) for land she did not own. The investigation further revealed she submitted forged 7/12 extracts to reduce her liability and deliberately entered incorrect mobile numbers and addresses to obstruct tracing.

The FIR was registered in August 2025, after the applicant had allegedly assisted in recovering Rs.12.98 lakh from three villages. However, the State contested this recovery, asserting the applicant had not deposited any amount herself and that the recovered sums were from other villagers. The applicant sought anticipatory bail, arguing her cooperation, clean record, and non-fleeing status warranted release.

The Legal Issue

Can anticipatory bail be denied to a public servant accused of large-scale economic fraud involving forged revenue records and misappropriation of public funds, solely on the ground that custodial interrogation is necessary to trace co-conspirators and recover proceeds, even if the accused claims cooperation and partial restitution?

Arguments Presented

For the Petitioner

The applicant’s counsel argued that she had voluntarily cooperated with the inquiry committee, facilitated recovery of Rs.12.98 lakh, and had no history of misconduct. She was a government servant with deep roots in the community, posing no flight risk. The counsel cited settled principles that bail is the rule and jail the exception, and that custodial interrogation is not automatically warranted merely because an offence is economic in nature. The recovery efforts and willingness to assist further investigation, the counsel submitted, rendered custody unnecessary.

For the Respondent/State

The State countered that the applicant’s role was central to the conspiracy. She was entrusted with preparing and verifying beneficiary lists, yet systematically inserted ineligible persons - including her own relatives and landlord - using forged documents and fake Aadhaar numbers. The investigation revealed Rs.5.78 lakh in fraudulent claims from witness statements alone, with an additional Rs.5.18 lakh from fabricated 7/12 extracts. The applicant had not deposited any amount herself, and her recovery claims were disputed. The State emphasized that the fraud spanned three years, involved multiple villages, and required custodial interrogation to identify associates, trace money flows, and uncover the full extent of the conspiracy.

The Court's Analysis

The Court began by acknowledging the general presumption in favor of bail but emphasized that economic offences, particularly those involving public funds, demand a distinct judicial approach. It relied on Supreme Court precedents in Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy and Nimmagadda Prasad, which categorize economic crimes as threats to national financial integrity due to their deliberate, calculated nature and systemic impact.

"An economic offence is committed with cool calculation and deliberate design with an eye on personal profit regardless of the consequence to the community. A disregard for the interest of the community can be manifested only at the cost of forfeiting the trust and faith of the community in the system to administer justice..."

The Court found the applicant’s conduct went beyond mere negligence or administrative lapse. She was not a passive participant but an active architect of the fraud: she used her official position to access and manipulate government databases, fabricated revenue records, and exploited loopholes in the system to route funds through fictitious beneficiaries. The inclusion of her own relatives and landlord demonstrated personal gain, not systemic pressure.

The Court rejected the applicant’s claim of cooperation as insufficient. While she had assisted in partial recovery, the State demonstrated that the recovered amount was not her own deposit but funds collected from other villagers. Crucially, she had not disclosed names of associates, the source of fake Aadhaar cards, or the individuals who helped forge documents. The investigation was still ongoing, with new witness statements emerging daily.

The Court held that the scale of the fraud - over Rs.25 crore - and the complexity of the conspiracy, involving forged documents, digital manipulation, and collusion across multiple talukas, made custodial interrogation indispensable. The applicant’s access to internal systems and knowledge of the modus operandi posed a clear risk of evidence destruction or witness tampering if released.

What This Means For Similar Cases

This judgment reinforces that in cases of large-scale economic fraud involving public funds, courts will prioritize investigative integrity over the presumption of bail, even when the accused is a government servant with no prior record. The mere assertion of cooperation or partial restitution will not suffice if the investigation is active and the accused holds key knowledge of the conspiracy.

Practitioners must now treat economic offences under BNSS Sections 316, 324, and 336, especially when involving forged revenue records or misuse of official access, as high-risk bail applications. The burden shifts to the applicant to demonstrate not just cooperation, but concrete, verifiable, and complete disclosure of all co-conspirators and financial trails. Absent such disclosure, courts are likely to uphold custodial interrogation as necessary.

The judgment also signals that courts will scrutinize recovery claims made by accused persons with skepticism, particularly when the recovered amount is not directly attributable to the accused’s own deposit. This may influence how prosecutors structure their opposition to bail applications in similar cases.

The scope of this ruling is limited to cases involving systemic fraud, forged documents, and public fund diversion. It does not extend to minor financial irregularities or cases where the accused has no access to sensitive systems or evidence.