The Bombay High Court has clarified that advances made on the basis of negotiable instruments such as cheques, excluding promissory notes, are excluded from the definition of 'loan' under Section 2(13)(j) of the Maharashtra Money Lending (Regulation) Act, 2014. This exclusion renders the bar under Section 13 of the Act inapplicable, preventing rejection of a plaint at the threshold under Order VII Rule 11 of the Civil Procedure Code. The Court emphasized that the burden lies on the defendant to prove the plaintiff is a licensed money lender, and such determination cannot be made summarily.

The Verdict

The plaintiff won. The Bombay High Court held that a suit based on dishonoured cheques and promissory notes cannot be rejected at the threshold under Order VII Rule 11 CPC merely because the plaintiff is alleged to be an unlicensed money lender. The core legal holding is that advances exceeding Rs. 3 lakhs made on negotiable instruments (other than promissory notes) are excluded from the definition of 'loan' under Section 2(13)(j) of the Maharashtra Money Lending Act, 2014. Consequently, Section 13's bar on decreeing claims by unlicensed lenders does not apply, and the plaint must proceed to trial.

Background & Facts

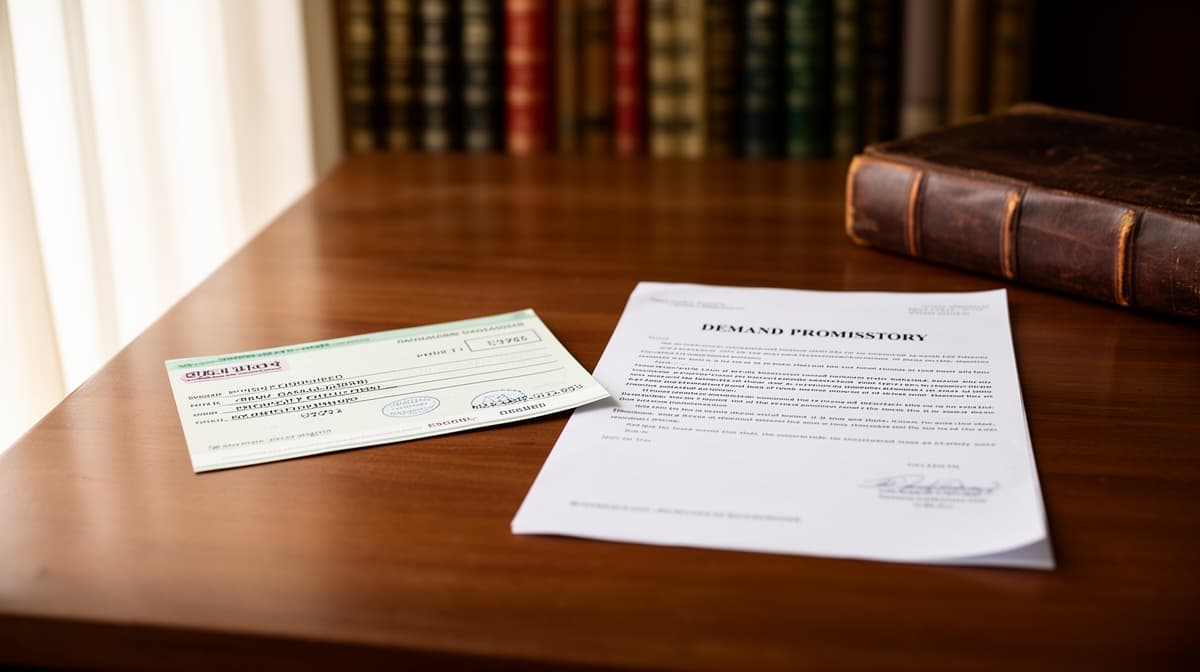

The plaintiff, Ashok Commercial Enterprises, filed a commercial suit against Hubtown Limited for recovery of Rs. 510 crores plus interest, based on dishonoured cheques and demand promissory notes issued by the defendant. The plaintiff alleged it had advanced short-term business loans between 2011 and 2018, with interest rates ranging from 21% to 36% per annum. The defendant issued post-dated cheques and promissory notes as repayment mechanisms. Two cheques dated 1st April 2018, for Rs. 68.92 crores and Rs. 499.92 crores, were presented and dishonoured for insufficient funds. The plaintiff also filed a criminal complaint under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act.

The defendant applied under Order VII Rule 11(d) CPC to reject the plaint, arguing that the plaintiff was engaged in the business of money lending without a mandatory license under the Maharashtra Money Lending (Regulation) Act, 2014. The defendant contended that the plaintiff's repeated lending at interest, coupled with the use of negotiable instruments, brought it squarely within the definition of 'money lender' under Section 2(13) of the Act. The defendant relied on precedents including Fauzan Shaikh and RBANMS Educational Institution to argue that the suit was barred under Section 13, which prohibits courts from passing decrees in favour of unlicensed money lenders.

The plaintiff opposed the application, asserting that its advances were made on the basis of negotiable instruments - specifically cheques - and therefore fell under the exception in Section 2(13)(j) of the Act. The plaintiff cited precedents such as Deepak Bhagwandas Raheja and Parekh Aluminex Ltd. to argue that the exclusion applies regardless of the interest rate or frequency of transactions, as long as the advance is tied to a negotiable instrument other than a promissory note.

The Legal Issue

The central legal question was whether an advance of money exceeding Rs. 3 lakhs, made on the basis of a negotiable instrument such as a cheque, constitutes a 'loan' under Section 2(13) of the Maharashtra Money Lending (Regulation) Act, 2014, or whether it is excluded by the exception in Section 2(13)(j). A secondary issue was whether the plaintiff’s alleged business of lending at high interest rates could justify rejecting the plaint at the threshold under Order VII Rule 11 CPC without a full trial.

Arguments Presented

For the Appellant/Petitioner

The defendant argued that the plaintiff’s repeated, interest-bearing advances to multiple parties over several years constituted a business of money lending under Section 2(13) of the Act. It contended that Section 2(13)(j) excludes only interest-free advances, and since the plaintiff charged up to 36% interest, the transactions were loans, not excluded advances. The defendant further argued that the use of promissory notes, which are not covered by the exception, rendered the entire transaction ineligible for exclusion. It relied on Fauzan Shaikh to assert that any advance at interest via negotiable instruments falls under the Act’s purview, and that the plaintiff’s deliberate omission of its unlicensed status amounted to suppression.

For the Respondent/State

The plaintiff countered that Section 2(13)(j) explicitly excludes advances made on negotiable instruments other than promissory notes, regardless of interest rate or frequency. It argued that the cheques issued were the basis of the debt, and thus the transaction fell squarely within the statutory exception. The plaintiff relied on Deepak Raheja to assert that the burden of proving the plaintiff is a money lender lies with the defendant, and that mere allegations of business lending are insufficient at the pleading stage. It further argued that the use of promissory notes did not negate the exclusion, as the suit was primarily based on cheques, which are covered by the exception.

The Court's Analysis

The Court undertook a detailed statutory interpretation of Section 2(13) of the Maharashtra Money Lending Act, 2014. It noted that the definition of 'loan' in Section 2(13) includes any advance at interest, but clause (j) carves out a specific exception: 'an advance of any sum exceeding three lakh rupees made on the basis of a negotiable instrument other than a promissory note'. The Court emphasized that this exception is not conditional on the absence of interest, but on the mode of transaction - namely, the use of a negotiable instrument.

"To put it in a nutshell, without a loan (as defined in the Money Lending Act of 2014 itself) being involved, there is no bar on any court to pass a decree."

The Court relied on the Division Bench decision in Deepak Bhagwandas Raheja, which held that the exclusion under Section 2(13)(j) applies even when interest is charged, provided the advance is made on a negotiable instrument other than a promissory note. The Court rejected the defendant’s reliance on Fauzan Shaikh, distinguishing it on the ground that Fauzan Shaikh dealt with the constitutional validity of the exception, not its applicability to cheques. The Court observed that accepting the defendant’s interpretation would render Section 2(13)(j) otiose, as it would nullify the legislature’s clear intent to exclude such transactions.

The Court further held that the plaintiff’s alleged status as a money lender - engaged in repetitive lending - could not be established at the threshold stage under Order VII Rule 11 CPC. The burden to prove the plaintiff is a money lender under the Act lies with the defendant, and such proof requires evidence on business continuity, system, and intent, which cannot be assessed summarily. The Court cited Khyati Realtors and Dahiben to underscore that rejection of a plaint is a drastic remedy, permissible only when the suit is manifestly barred or fictitious on its face. Here, the pleadings disclosed a claim based on negotiable instruments, which the statute explicitly excludes from the definition of 'loan'.

What This Means For Similar Cases

This judgment provides critical clarity for practitioners handling recovery suits based on dishonoured cheques. It confirms that Section 2(13)(j) of the Maharashtra Money Lending Act operates as a shield against the bar under Section 13, even when high interest rates are charged. Practitioners may now confidently file suits based on cheques without fear of summary rejection on grounds of unlicensed money lending, provided the transaction is not tied to a promissory note.

The ruling reinforces that allegations of being a 'money lender' must be substantiated with evidence of business continuity and system, not merely inferred from multiple transactions. At the Order VII Rule 11 stage, courts must not engage in fact-finding or weigh evidence. This limits the scope for defendants to use licensing violations as a procedural weapon to derail legitimate claims.

However, the judgment does not immunize plaintiffs from liability. If evidence at trial establishes that the plaintiff is a licensed money lender and the transaction was a disguised loan, the defendant may still raise the bar under Section 13. The judgment also does not extend to promissory notes, which remain within the definition of 'loan' under Section 2(13). Practitioners must therefore carefully structure documentation: cheques and bills of exchange are protected; promissory notes are not.