The Andhra Pradesh High Court has delivered a definitive ruling that long-term possession of government land, even for over a century, does not entitle occupants to compensation under the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013. The judgment clarifies that legal ownership or recognized title is a non-negotiable precondition for claiming benefits under the Act, rejecting the notion that historical occupation alone can create vested rights.

Background & Facts

The Dispute

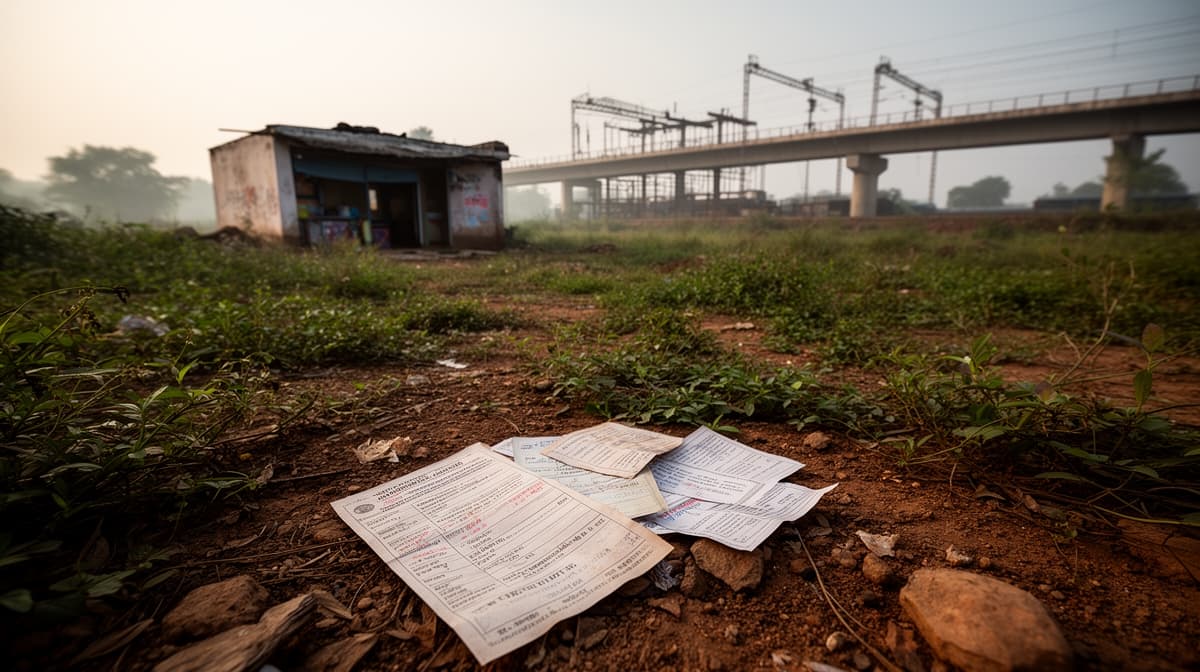

The petitioners, residents of Gunadala in Vijayawada, claimed ancestral possession of land in Survey Number 284/4 for over 100 years. They asserted that their forefathers had lived and operated small businesses on the land, paying property taxes to the Gram Panchayat before its merger into the Vijayawada Municipal Corporation in 1981. They were later informed that their structures stood on government poramboke land and were to be evicted for the construction of a railway overbridge (ROB).

Procedural History

- 2020: Multiple writ petitions filed before the Andhra Pradesh High Court seeking compensation under the 2013 Land Acquisition Act.

- 14.09.2020: Court directed authorities to follow due process before eviction.

- 2022: Respondents issued notices to petitioners and allotted 88 housing units to encroachers under JNNURM+3Housing scheme on payment of Rs. 66,000 per unit.

- 2023: Contempt petitions filed against officials for alleged non-compliance with interim orders.

Relief Sought

The petitioners sought a declaration that they were landowners under Section 3(r) of the 2013 Act, a direction to initiate acquisition proceedings, and payment of fair compensation. They argued that their continuous, uninterrupted possession, tax payments, and utility connections established their entitlement.

The Legal Issue

The central question was whether long-term, unchallenged possession of government poramboke land, without any titled document, pattas, or legal regularization, qualifies an occupant as a "landowner" under Section 3(r) of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013.

Arguments Presented

For the Petitioner

The petitioners relied on LAO-Cum-RDO v. Mekala Pandu to argue that even encroachers are entitled to notice and due process. They contended that Section 3(n) of the Act, which defines "holding of land" to include occupants, and Section 3(r), which defines "landowner" broadly, should be interpreted liberally to protect the poor and marginalized. They emphasized that payment of property tax, electricity, and water bills, along with generational occupation, established de facto ownership.

For the Respondent

The State countered that Section 3(r) explicitly limits "landowner" to those with recorded title, pattas, court orders, or forest rights under the 2006 Act. The respondents cited G. Ramunaidu & Others v. Principal Secretary, Revenue Department to argue that possession without legal title cannot be equated with ownership. They stressed that poramboke land is state property, and tax payments or utility connections confer no legal interest. The State also highlighted that humanitarian housing was already provided to 114 affected families.

The Court's Analysis

The Court undertook a strict textual interpretation of Section 3(r) of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013. It held that the provision’s four clauses are exhaustive and require either recorded ownership, pattas, court declarations, or forest rights. The petitioners failed to produce any such document.

"A plain reading of this provision will bring within its ambit, only such persons, who are either having de jure title to the land or such persons who would be entitled to grant title over the land."

The Court distinguished between possession and ownership, emphasizing that illegal encroachment does not ripen into legal title merely through duration. It rejected the argument that tax payments or utility connections create vested rights, noting that these are administrative conveniences, not legal titles. The Court also affirmed that the Act is a beneficial legislation meant for legitimate landowners, not illegal occupants.

The Court further noted that the State had already fulfilled its humanitarian obligations by allotting 88 housing units to affected encroachers under a welfare scheme. The absence of legal title meant the petitioners could not invoke the statutory compensation mechanism.

The Verdict

The petitioners lost. The Court held that mere long-term possession of government land without title, pattas, or regularization does not confer landowner status under Section 3(r) of the 2013 Act. The writ petitions and contempt cases were dismissed with no costs.

What This Means For Similar Cases

Possession Without Title Is Not Enough

- Practitioners must now establish that claimants hold recorded title, pattas, or a court declaration to claim compensation under the 2013 Act.

- Arguments based on tax payments, utility connections, or generational occupation will not suffice unless accompanied by formal regularization.

State’s Humanitarian Measures Do Not Create Legal Rights

- Offering alternate housing under welfare schemes does not imply recognition of legal title.

- Such measures are discretionary and cannot be converted into statutory entitlements by petitioners.

Due Process Still Applies to Evictions

- Even illegal encroachers are entitled to notice and hearing before eviction, as affirmed by the Court’s prior order.

- Authorities must document and follow procedural fairness, but this does not equate to compensation liability.