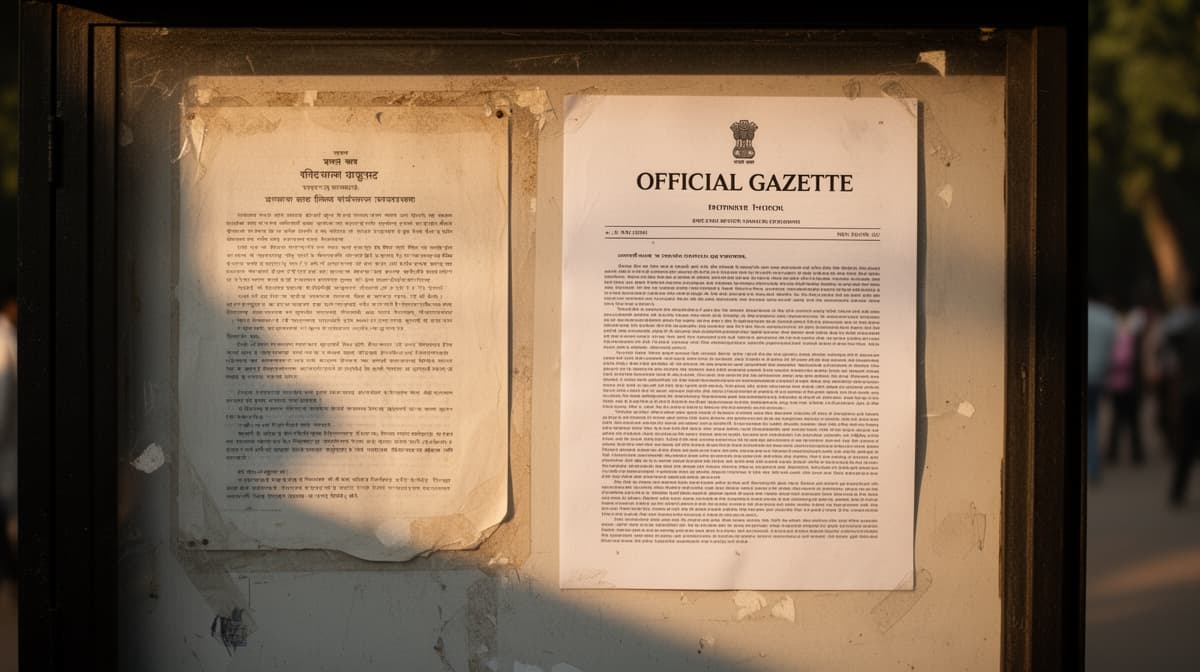

The Supreme Court has delivered a definitive ruling affirming that delegated legislation, including trade restrictions like Minimum Import Price (MIP) notifications, acquires legal force only upon publication in the Official Gazette. This judgment reinforces the constitutional principle that laws cannot bind citizens until they are formally promulgated through the legally prescribed channel, safeguarding commercial certainty and the Rule of Law.

Background & Facts

The Dispute

The appellants, private importers of mild steel products, entered into firm sale contracts with Chinese and South Korean suppliers between 29 January and 4 February 2016. On 5 February 2016, they opened irrevocable letters of credit (LCs) to finance these imports. On the same day, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) uploaded a Notification on its website imposing a Minimum Import Price (MIP) on 173 HS-coded steel products. The Notification explicitly stated it was 'To be published in the Official Gazette of India'. It was formally published in the Official Gazette on 11 February 2016.

Procedural History

- 5 February 2016: Appellants opened irrevocable LCs; DGFT uploaded MIP Notification online

- 8 February 2016: Appellants applied for LC registration under transitional protection under para 1.05(b) of the Foreign Trade Policy (FTP)

- 11 February 2016: MIP Notification published in the Official Gazette

- 2018: High Court of Delhi dismissed writ petitions, holding that the 'date of Notification' was 5 February 2016, not 11 February 2016

- 2026: Appeals filed before the Supreme Court

Relief Sought

The appellants sought quashing of the Notification or, alternatively, a declaration that the MIP does not apply to LCs opened before 11 February 2016, invoking the transitional protection under para 1.05(b) of the FTP.

The Legal Issue

The central question was whether the expression 'date of this Notification' in para 2 of the MIP Notification refers to the date of its online upload or the date of its formal publication in the Official Gazette under Section 3 of the Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act, 1992.

Arguments Presented

For the Appellant

Learned senior counsel argued that delegated legislation must strictly comply with the parent statute’s mandate of publication in the Official Gazette to become enforceable. Reliance was placed on B.K. Srinivasan v. State of Karnataka and Harla v. State of Rajasthan, emphasizing that publication is not a mere formality but a constitutional prerequisite for legal effect. The Notification itself acknowledged its incomplete status by stating it was 'to be published', confirming that legal force had not yet accrued on 5 February 2016. Para 1.05(b) of the FTP, incorporated into para 2 of the Notification, clearly entitles importers to protection if LCs were opened before the date of imposition of restriction - which, legally, was 11 February 2016.

For the Respondent

The Union contended that the 'date of Notification' was 5 February 2016, the date of upload, and that the benefit of transitional protection should be limited to LCs opened before that date. It analogized the situation to the Land Acquisition Act, 2013, where enactment and enforcement dates differ. It further argued that the FTP is merely a policy document and cannot override a statutory Notification, and that para 1.05(b) only applies if LCs are registered with the Regional Authority - a condition not fulfilled.

The Court's Analysis

The Court undertook a rigorous analysis of the statutory framework under Section 3 of the Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act, 1992, which mandates that any order regulating imports must be 'published in the Official Gazette'. The Court held that this requirement is not procedural but substantive: it transforms executive intent into binding law. The Court rejected the notion that website publication could substitute statutory publication, citing Harla v. State of Rajasthan and Gulf Goans Hotels Co. Ltd. v. Union of India to affirm that natural justice demands notice through a recognized, public channel.

"The requirement of publication in the Gazette... is not an empty formality. It is an act by which an executive decision is transformed into law."

The Court emphasized that the Notification’s own language - 'To be published in the Gazette' - constituted an admission that it lacked legal force prior to 11 February 2016. To hold otherwise would permit the executive to impose burdens retroactively, violating the Rule of Law. The Court also rejected the argument that the FTP was subordinate to the Notification, noting that para 2 of the Notification explicitly incorporated para 1.05(b) of the FTP, making it an integral part of the transitional relief. Denying the benefit would undermine the very purpose of the FTP: to ensure predictability in foreign trade.

The Verdict

The appellants won. The Supreme Court held that the date of Notification under Section 3 of the Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act, 1992 means the date of publication in the Official Gazette, not the date of online upload. The MIP cannot be applied to imports covered by LCs opened before 11 February 2016, and the appellants are entitled to the transitional protection under para 1.05(b) of the FTP.

What This Means For Similar Cases

Publication Is the Sole Trigger for Legal Effect

- Practitioners must challenge any administrative order claiming effect before Official Gazette publication

- Online portals, press releases, or email notifications cannot substitute statutory publication

- Any penalty or restriction imposed before Gazette publication is void ab initio

Transitional Protections Are Integral to Regulatory Clarity

- When a policy incorporates transitional clauses (e.g., para 1.05(b)), courts will interpret them purposively to protect legitimate commercial expectations

- Importers who act in good faith based on prior free trade status are shielded from sudden regulatory changes

- The burden shifts to the State to prove that the affected party had actual, timely notice through legally recognized channels

Delegated Legislation Must Be Construed Strictly Against the State

- Ambiguities in delegated legislation are resolved in favor of the regulated party

- The State cannot use technicalities to expand the scope of restrictions beyond what is expressly provided

- Courts will invalidate attempts to retroactively apply restrictions where the parent statute requires formal publication