The Madras High Court has held that conditions imposed in criminal summonses, particularly financial bonds, must be proportionate to the accused’s economic capacity. The court modified a Rs.20,000 bond requirement for a daily wage earner to Rs.5,000, emphasizing that procedural fairness under the BNSS Act, 2023 cannot override the constitutional guarantee of reasonable procedure.

The Verdict

The petitioner won. The Madras High Court modified the bond condition in a summons issued under the BNSS Act, 2023, reducing the required security from Rs.20,000 to Rs.5,000 with two sureties. The court held that imposing financially onerous conditions on an indigent accused violates the principle of proportionality and Article 21 of the Constitution. The direction ensures that summonses remain a tool for ensuring appearance, not a mechanism of economic exclusion.

Background & Facts

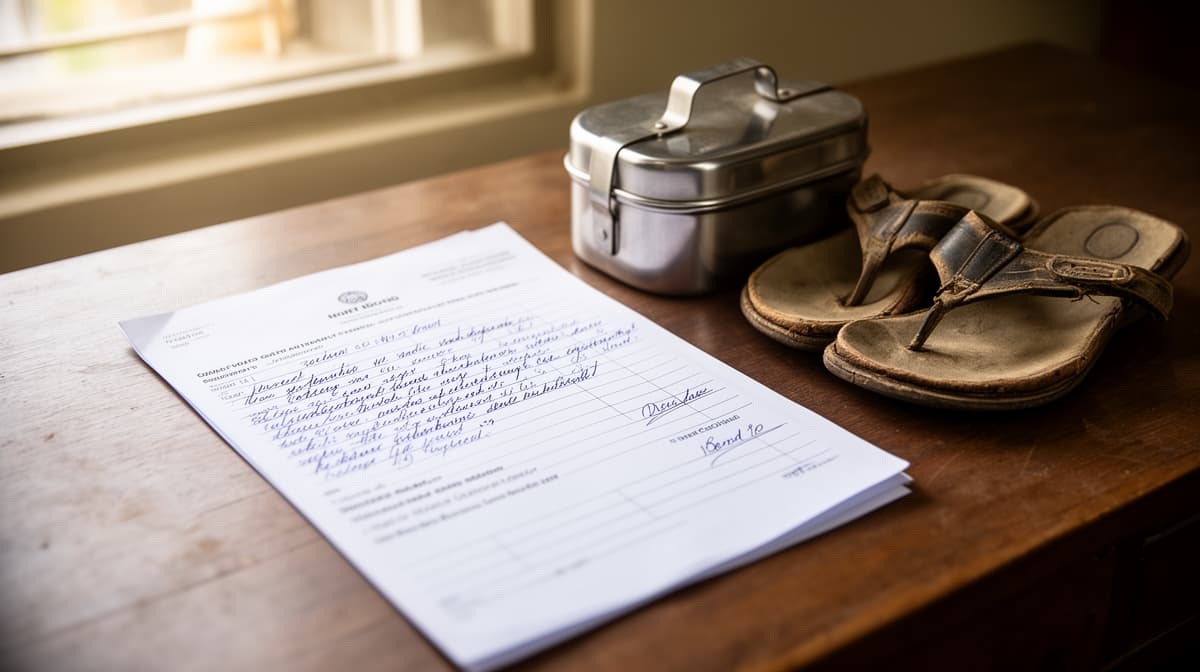

The petitioner, M. Senthilkumar, was named as Accused No.7 in a criminal case registered by the Central Bureau of Investigation under R.C. No.15/A/2017. The case alleged criminal conspiracy and cheating of Canara Bank, involving a Rs.5 lakh loan obtained through allegedly forged documents. The petitioner claimed he received only half the loan amount, with the rest diverted by a broker, and that he had no role in the fabrication of documents.

The XI Additional Special Judge for CBI Cases issued a summons on 18 November 2025, requiring the petitioner to appear in person on 24 November 2025. The summons imposed two conditions: execution of a bond for Rs.20,000 with two sureties, and mandatory production of original Fixed Deposit Receipts for non-blood relatives. Online FDRs were explicitly rejected.

The petitioner, a daily wage earner with no blood relatives available as sureties, filed a criminal original petition under Section 528 read with Section 483(b) of the BNSS Act, 2023, seeking modification of these conditions. He submitted that he had cooperated fully with the investigation since the FIR was registered in 2017, never absconded, and would appear before the court on all dates.

The CBI opposed the modification, arguing that the nature of the offence - cheating a public sector bank - warranted strict compliance to ensure trial integrity. However, it did not dispute the petitioner’s financial status or his consistent cooperation.

The Legal Issue

The central question was whether a court issuing a summons under the BNSS Act, 2023 may impose a bond amount that is disproportionate to the accused’s economic capacity, particularly when the accused is not a flight risk and has demonstrated cooperation with the investigation.

Arguments Presented

For the Petitioner

The petitioner’s counsel argued that the Rs.20,000 bond requirement was manifestly onerous for a daily wage earner with no fixed income. He cited Section 483(b) of the BNSS Act, 2023, which empowers the High Court to exercise inherent powers to prevent abuse of process or secure the ends of justice. He further relied on Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to a fair and reasonable procedure. The petitioner had no blood relatives to act as sureties, and the requirement of original FDRs for non-relatives imposed an additional, unreasonable financial burden. He emphasized that the accused had never evaded summons and had no history of non-appearance.

For the Respondent

The Special Public Prosecutor for CBI Cases contended that the offence involved cheating of a public sector bank through forged documents, which warranted stringent conditions to ensure the accused’s presence. He argued that the bond amount was not excessive in the context of the alleged loss to the bank and that the conditions were standard in CBI cases. He did not dispute the petitioner’s financial hardship but maintained that procedural rigour was necessary to deter evasion in economic offences.

The Court's Analysis

The court rejected the notion that the gravity of the alleged offence justifies disproportionate procedural burdens on an accused who is not a flight risk. It observed that summonses are not bail orders and are meant to secure attendance, not to impose financial penalties. The court noted that the petitioner had cooperated with the investigation for eight years, never absconded, and had a permanent address. These factors negated any reasonable apprehension of non-appearance.

"The requirement of a bond of Rs.20,000/- with original FDRs from non-blood relatives, in the case of a daily wage earner with no financial means, is not merely inconvenient - it is oppressive and violates the principle of proportionality under Article 21."

The court held that the BNSS Act, 2023, while codifying procedural norms, does not authorize courts to impose conditions that effectively penalize poverty. It distinguished this case from those involving accused persons with means or a history of evasion, noting that the purpose of a bond in a summons is not deterrence but assurance of appearance.

The court further clarified that the requirement of original FDRs, while intended to prevent fraud, could not override the constitutional right to access justice. The court accepted the petitioner’s undertaking to appear on all dates as sufficient guarantee, rendering the original bond condition unnecessary.

What This Means For Similar Cases

This judgment establishes a clear precedent that bond conditions in summonses must be proportionate to the accused’s economic status. Practitioners can now invoke this ruling to challenge excessive financial conditions imposed on indigent accused persons, particularly in cases where there is no evidence of flight risk or non-cooperation.

The ruling reinforces that courts must balance procedural requirements with constitutional rights under Article 21. It limits the scope for mechanical application of standard bond amounts in CBI or economic offence cases. Future applications for modification of summons conditions should now include affidavits of income and proof of cooperation with investigation.

This decision does not apply to accused persons who have previously absconded or shown hostility to the process. However, for first-time, cooperative accused with limited means, the threshold for modifying bond conditions is now significantly lowered. Courts are now expected to conduct a case-specific inquiry into financial capacity before imposing any monetary condition.